The government had offered them both not only safe refuge, but also the prospect of a doctorate. Sana Al-Mudhaffar is an economist, her husband a pharmacist. When she became pregnant, the promise proved to be null and void. The Berlin authorities - she had wanted to do a doctorate at the Berlin School of Economics - told her that she could stay, but that the child would have to leave the country as soon as it was born.

From one moment to the next, her plans for a future in the GDR were shattered - even though Al-Mudhaffar was a convinced communist. Looking back, she is still outraged:

No day care place, no apartment, no room, no right to remain. No right to remain! The child must leave the GDR! And so I said: No! Is that your idea of solidarity?

Original soundbite Sana Al-Mudhaffar

So the family decided to leave the country again. Suddenly, however, Jenapharm demanded Al-Mudhaffar's husband stay, because his expertise as a pharmacist was needed. And suddenly, their child was also allowed to stay.

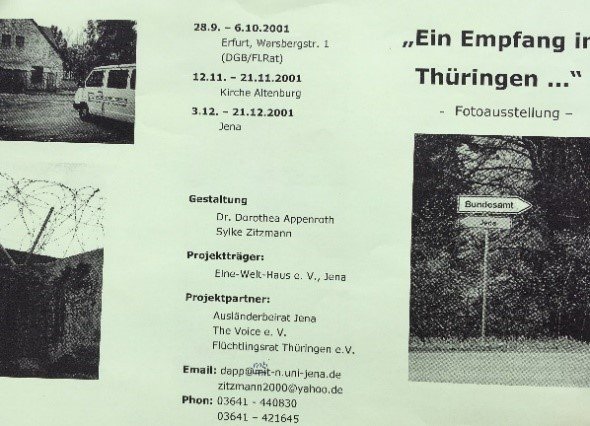

In 1983, the family moved to Jena, Sana Al-Mudhaffar's husband did research at Jenapharm, and she herself got a job at the company. She was however never to do a doctorate. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, her language skills brought her to asylum counselling, and she worked for the initiative Asyl e. V. (Citizens' Initiative for Asylum) for many years. Today she is one of the most knowledgeable experts on asylum and migration policy in Jena.